Alignment Infrastructure with Agentic Software Engineering

Table of Contents

Challenge and Opportunity

Coding agents have fundamentally changed both the mechanics and the economics of software engineering: knowing the syntax and idiosyncrasies of programming languages has become less useful; what once took weeks now takes days, what took days now takes hours.

This acceleration brings opportunities but also obvious challenges:

Large refactorings can now be contemplated. Changes that would have consumed a team for a quarter can be prototyped in days.

Meticulous tasks are much easier. Careful analysis of edge cases and test case coverage can be aided.

Cohesiveness is the biggest concern. When everyone can produce more, ensuring it all fits together becomes the critical challenge.

Quality is a real risk. More code, faster, means more opportunities for defects to slip through. Human work is relegated to reviewing. Attention decreases and subtle bugs get introduced. Context windows shrink; bugs once fixed get re-introduced.

Costs should be measured differently. The bottleneck has shifted from writing code to reviewing, testing, and integrating it.

Avoiding Everyone Pulling in Different Directions

After your team is properly set up with these new tools and adopts an initial set of best practices (see Foundations), they will most likely experience the alluring appeal of these new powers.

The temptation for developers is real: five terminal windows open, each with an AI assistant churning out PRs. The productivity feels intoxicating. But productivity without alignment is just organized chaos.

When every engineer can ship 3x more code, the coordination overhead doesn’t scale linearly—it scales exponentially. Just because one can, doesn’t mean one should: more PRs mean more reviews. More changes mean more integration conflicts. More features mean more architectural decisions that need to stay coherent.

Taking Advantage Of This New Power

At the same time, we should not throw out the baby with the bathwater. What used to be difficult to change might no longer be (see the definition of Architecture). These new capabilities can challenge the existing architectures and paradigms in healthy ways.

Consider the architectural debate that used to consume a team for days: should we refactor the payment module to use the new event-driven pattern, or is the risk too high? In the old world, this was a battle of intuition and experience. Senior engineers would argue based on past projects. Diagrams would be drawn. Meetings would multiply. Eventually, someone with enough authority would make a call, and everyone would hope it was right.

Now you can just build it and see.

When a prototype takes hours instead of weeks, “let’s try both approaches” becomes a legitimate strategy. The team can spike two implementations, compare them on actual metrics (performance, test coverage, code complexity) and decide based on evidence rather than speculation.

This changes the risk calculus entirely:

Bold refactors become feasible. Every codebase has that module everyone’s afraid to touch. When you can prototype the refactor in a day, you can validate the approach before committing the team to months of migration work.

Architecture debates become empirical. REST vs. GraphQL? Monolith vs. microservices for this component? Build minimal versions of both, measure what matters, decide with data.

Throwaway prototypes become routine. Building something you might discard was always theoretically good practice but economically hard to justify. Now it’s cheap enough to do regularly.

The cost of being wrong drops. If an agent can build it in hours, it can rebuild or revert it too. Recovery is no longer a months-long project.

When you have clear guidelines, early feedback loops, and a framework for tracking experiments, you can afford to run multiple parallel explorations. Without investing in this alignment infrastructure, parallel experimentation would be chaos. With it, it’s a competitive advantage.

The organizations that grasp this will move faster not by typing faster, but by deciding faster—replacing speculation with evidence, and debate with data.

How LLMs Can Help Balance Cohesion and Experimentation

Fortunately, the same AI capabilities driving this acceleration can help manage it. But only if we think beyond simple code generation or automated PR reviews.

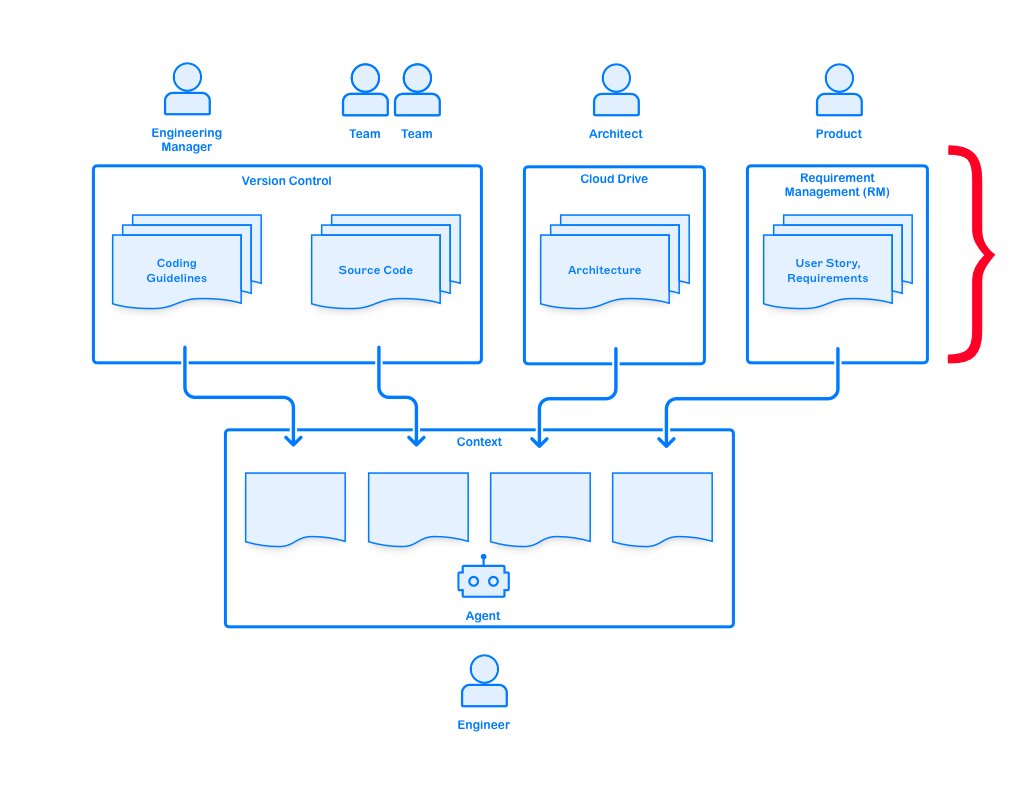

Stakeholders Publish Guidelines for Engineers to Pull

Agents across your team need to be given the same materials in order to stay aligned. These should include:

- Coding guidelines, including stylistic, security related, infrastructure, etc…

- Engineering principles, both general but specific to the phase of this project or product

- Product requirements (see User Story),

- UX guidelines, style guides

- Architecture documents including non-functional requirements, error handling and performance goals (see Architecture).

Technically, this is no different than developing without agents. Whereas we expect engineers to absorb this content and apply it during development, providing it to agent is now critical to ensure alignment. Agents cannot read your mind and distinguish between a “quick and dirty” script or the beginning of a large and important codebase, unless of course, you tell them.

Identify these artifacts and their owners. Disseminate them hierarchically following your organization structure, or better yet, encourage a pull model through a merit-based “marketplace”. The key is to ensure engineers know how to discover them and where to get them from.

At first, you might need tooling that fetches requirements from your Requirement Management system (JIRA, Azure DevOps, …) into the repo. Although, as you will see later, we recommend working directly in the version control system.

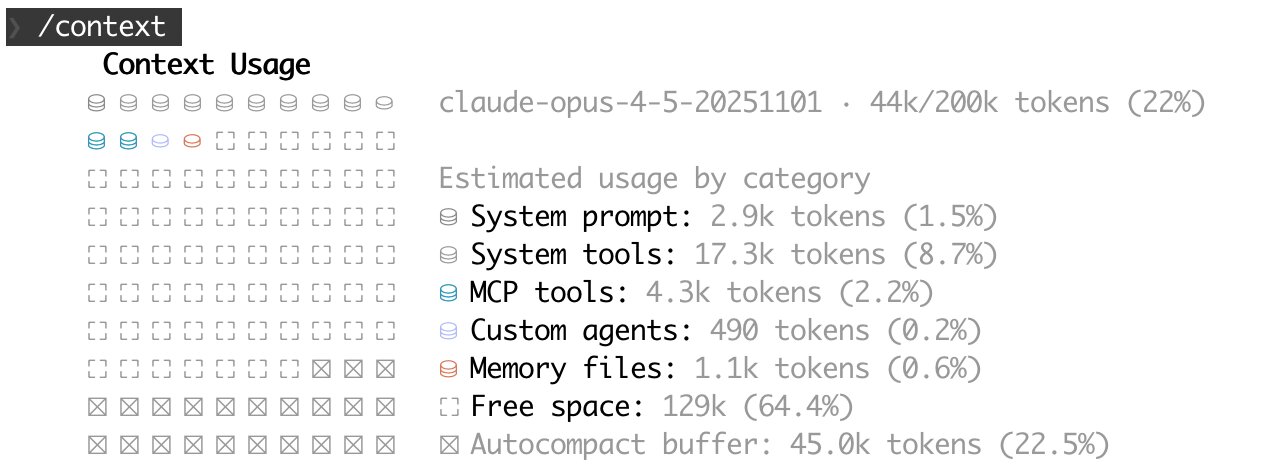

Boiling Down to the Essence to Manage Context Size

LLMs operate with a finite context of tokens. The more tokens are used up with background, constraints or direction, the fewer will be available to solve the task at hand. So, carefully managing this space, by including relevant content, without bloating it is a critical skill of agentic engineering.

LLMs already know some generic software engineering practices, since it is part of their training dataset. So, prioritize sharing project-, team-, or company-specific guidance to maximize applicability.

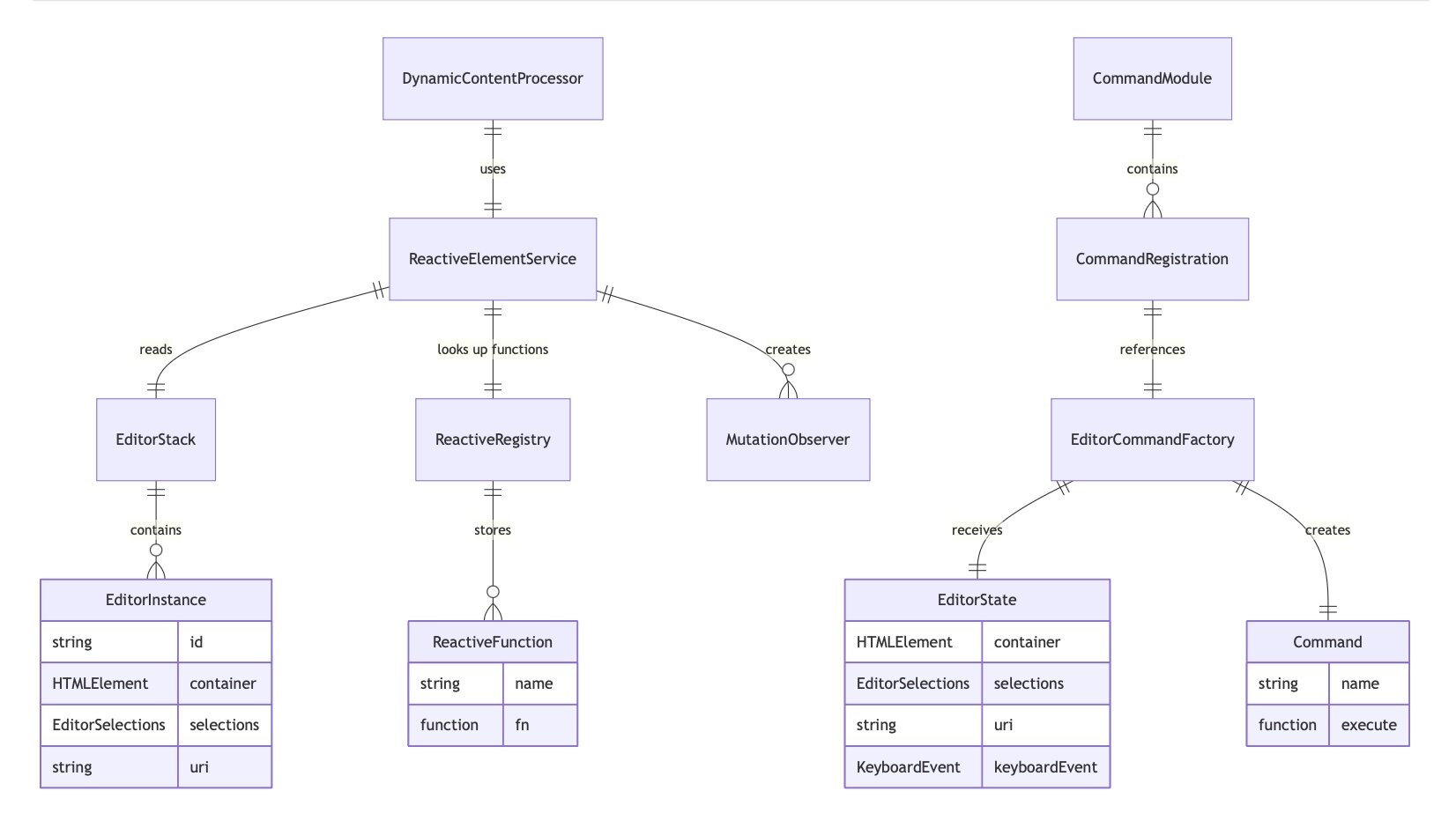

Text based content (guidelines, principles, requirements, etc…) are easy to provide the agent during the planning phase. And while agents are capable of interpreting images, a better approach is to convert diagrams and visual content to text, and generate representations for human consumption from those.

Here’s an example of an Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD) generated from a short markdown section of a few dozen lines, using the opensource MermaidJS software, now the de facto and most widely supported tool for displaying diagrams in markdown:

erDiagram

EditorStack ||--o{ EditorInstance : contains

EditorInstance {

string id

HTMLElement container

EditorSelections selections

string uri

}

# etc...

If converting to text is not an option, LLMs can help maintain different formats synchronized. Too often, we have refrained from converting a document to another format (eg. text) out of fear that changes to this exported version would be difficult to re-incorporate in the source document. Agents can convert between formats, or even make edits to a diagram in a visual application using MCP servers (eg. Figma, LucidChart, Sketch all provide MCP servers).

Iterate through Version Control

This process is iterative and will require trial and error. So, as the team discovers what works and what doesn’t, being able to propose changes to the owners or merely ask questions is critical. The best approach for this is to convert all artifacts to version control.

This will allow changes to compound (see Compounding) as incremental improvements are discovered and disseminated back to the team.

Better yet, transition your organization’s stakeholders to work directly in version control.

Various solutions exist to pull this context before firing up the agent. Use

git submodules, or simply symlinking between repositories.

Boris Cherny, the inventor of Claude Code, recently published his team’s workflow, which includes putting the agent’s “master guideline file” (ie. CLAUDE.md) under version control. Different agents have different methods of managing guidelines, but the concept is similar.

Describe Adherence and Deviations

An under-appreciated feature of LLMs is their ability to truly digest and interpret the language. As a result, the importance and criticality of following a particular rule can also be expressed in plain English, so that an agent can weigh whether a departure is warranted or not.

Security guidelines should probably be expressed using the strongest possible language (“NEVER publish passwords or tokens”, “ALWAYS verify that no keys are committed”, etc…), but using an external library over rebuilding one is a preference that depends on the specific situation.

The good ol’ RFC

2119, defining meanings of MUST, MUST NOT, SHOULD SHOULD NOT, etc…

can come in handy here.

Guidelines for handling deviations can also be expressed. For example, “in doubt, send an inquiry message to the @architect Slack channel”, or “file an architecture review ticket”, assuming you’ve equipped your agent with the appropriate MCP servers.

Provide Early and Periodic Feedback to Engineers

Long running PRs have always been dangerous, and are now even more so. Changes can get messy quickly, as LLMs tend to go for “working code”, over more sophisticated but more maintainable solutions. The risk of large merge conflicts is one thing, but more dangerous is a subtle but fundamental departure in a mental model (eg. data, service or component architecture). It is easier than ever to get over one’s skis.

Luckily, checking the adherence of an ongoing branch is easier to do today using LLMs. Consider asking your engineers to perform adherence checks periodically, perhaps using a subagent with a skill tailored to this task. Or, automate this process for each published branch, alerting owners of suspicious deviations early on.

Of course, this requires partial commits and pushes, even more important now than before. But both engineer and reviewer can ask the agent to summarize the state of changes, the risks and opportunities, without needing to comprehend intermediate work.

One might need to instruct the agent to be “adversarial”, or “honest” to avoid its agreeable or sycophantic nature, built-in by design to increase engagement (see “Smart people get fooled by AI first” about the very real problem of AI psychosis).

Or rather than asking one-sided questions, remember to ask for both sides of a question. For example, instead of:

Does this plan follow our established patterns?

ask:

Identify where this plan follows established patterns and where it diverges.

Automated PR reviews that just check for bugs miss the point. The real value is in checking for alignment early in the feature lifecycle.

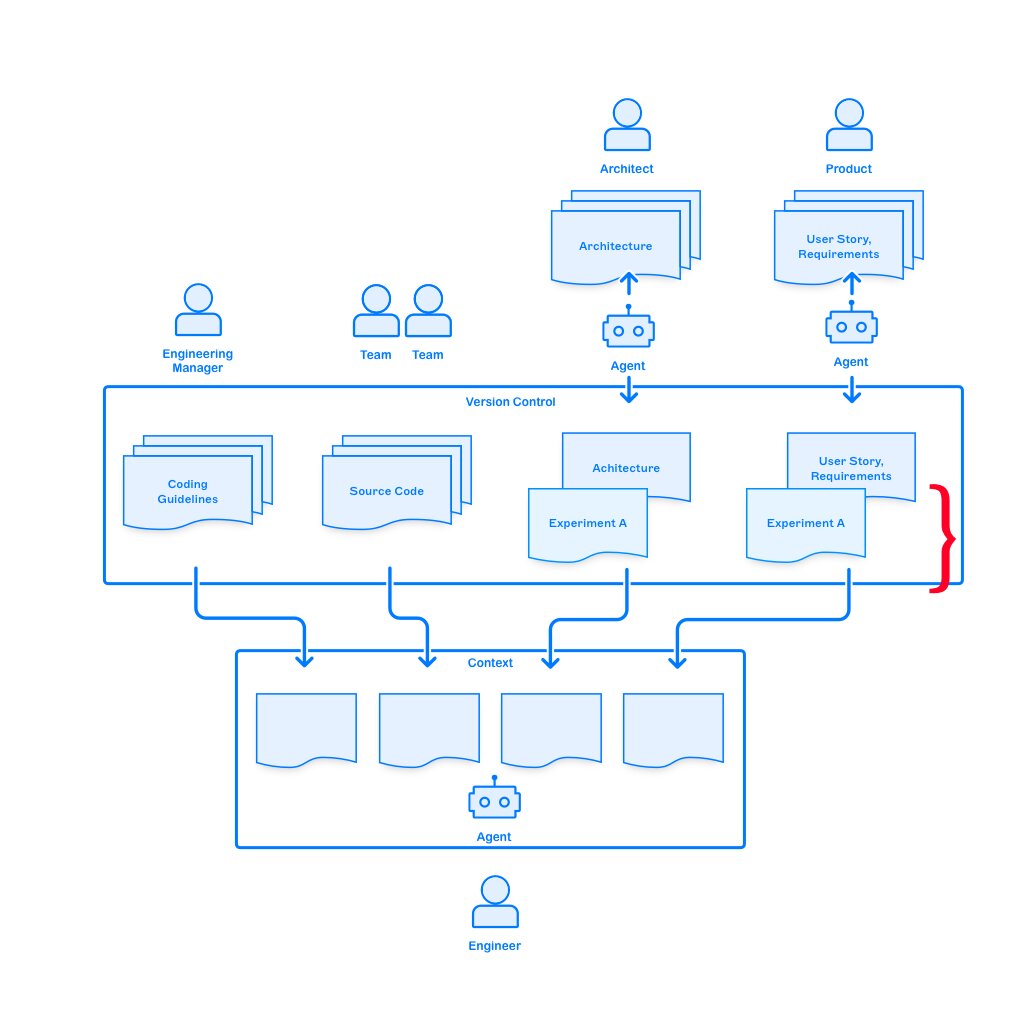

PR for Small Changes, Long running Branches for Experiments

Not every departure is a mistake. Experiments are important, as we don’t always know ahead of time what to build. But departures should be visible, not hidden in a sea of commits.

When someone intentionally breaks from the established pattern, treat it as an experiment:

- Document the hypothesis: why might this approach be better?

- Define success criteria: how will we know if it worked?

- Set a review date: when will we evaluate the results?

- Make a decision: adopt the new pattern, or revert to the old one?

This turns potential drift into deliberate evaluation.

With the confidence in place that departures are identified early, architects and product managers can agree to devote cycles to experiments. They can be tracked in branches, across multiple repositories, and infrastructure deployed to carry them along.

This allows product or architectural data-driven decisions to be made by comparing empirically built code and production metrics.

The Need for Human Decisions Increases

As it becomes faster and cheaper to do more things, we need to ensure more frequently that we are still on track and not drifting. Yes, this means more decision points but AI can make those decisions faster and better.

Shorter, More Frequent and Better

In addition to using AI to take meeting notes, ask agents to summarize past decisions, current status, completed and open action items.

When a decision is reached, use version control to track it, along with the observations made of the data, the unvalidated assumptions, the arguments in favor or against, as well as the participants.

All of this information is useful when asking LLMs to summarize it back at the next decision point. And as new data is collected from experiments, past decisions may no longer be valid; re-evaluating them is also something LLMs can help with.

Relying More on First Principles, Strategy and Values

As agents solve more mechanistic problems, understanding and applying the mental models, patterns, and principles that drive decisions becomes increasingly critical: algorithmic thinking, data science fundamentals, cost-performance tradeoffs, quality models like code coverage or static code analysis, and operational metrics, are all concepts that every team member should embrace, as they become the new language to master.

The more honestly an organization can share its business strategy, the better decisions can be made at every level. This means making explicit the drivers that actually matter: cost, quality, velocity, growth, or team retention. When these values remain implicit or unarticulated, agents and teams alike will optimize for the wrong things or make inconsistent choices based on incomplete context.

Organizations with strongly embodied values avoid flip-flopping on decisions. When principles are clear and internalized across the organization, they serve as a stabilizing framework for evaluating tradeoffs—whether the decision-maker is a person or an agent. Without this grounding, each new situation invites re-litigation, and the proliferation of agentic tools only amplifies the resulting inconsistency.

Human Judgment More Important

The irony of AI-accelerated development is that it makes human judgment more important, not less. When anyone can produce code quickly, the differentiator becomes which code to produce.

This means investing in:

- Clear decision frameworks that help teams evaluate trade-offs consistently

- Documented principles that guide choices before they’re made

- Regular alignment practices that keep everyone pointed in the same direction

- Feedback loops that surface problems before they compound

The teams that thrive won’t be the ones that produce the most code. They’ll be the ones that maintain cohesion while moving fast. They’ll use AI not just to accelerate production, but to accelerate alignment.

Working with these new tools as an individual contributor is exhilarating. The question is whether your team practices can scale alongside these new powers—and reap the rewards.

Want to Work Together?

Let's discuss how my experience can help your organization.

Get In Touch